This near-miraculous soil enhancer is slowly finding an audience in our region – and maybe even some local producers.

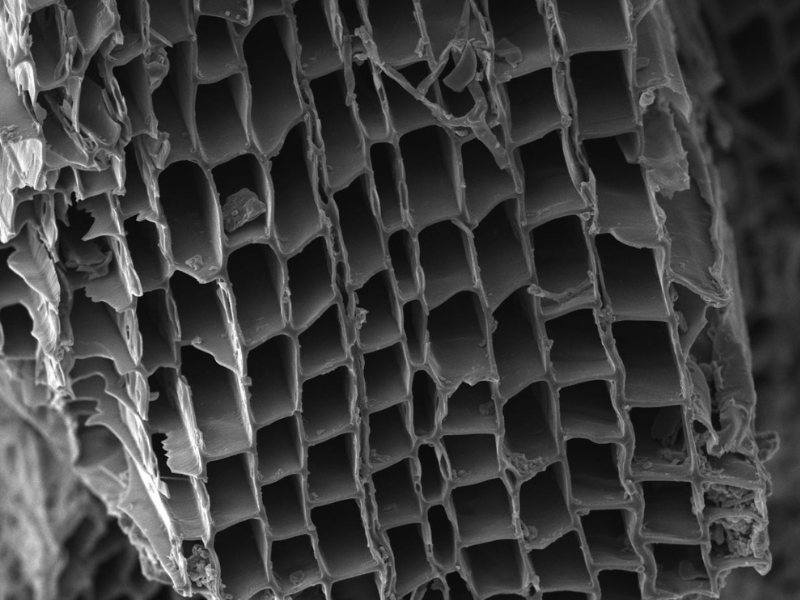

It may look like an ugly pile of charcoal, but it’s not – it’s biochar, a near-miraculous soil enhancer whose power is hidden in the billions of microscopic “cells” that comprise its structure. It’s slowly finding an audience with farmers in Mendocino and Lake counties, and through the combined efforts of local business leaders, researchers, and farmers, it could soon become more widely available.

But first things first – what is biochar exactly? It’s a form of pure carbon that’s made by taking biomass material such as tree branches, nut shells, and lumber waste and heating it in a temperature-controlled (350-700 degrees Celsius), low-oxygen environment for a certain amount of time. After it’s watered down and cooled, it’s crushed into small pellets, and typically mixed with compost for maximum effectiveness.

Although biochar may look like charcoal, the pyrolysis process used to create it results in a by-product that is far more porous and stable than charcoal. Which is why it’s known as “black gold” to farmers: biochar’s millions of tiny cells act as a sponge and help soil retain water, nitrogen, nutrients, and beneficial microorganisms. And once it’s tilled into the soil, its effects last for decades, and possibly centuries, making it a near-permanent way to improve soil. In fact, there is evidence that as long as 2500 years ago biochar was used to improve the soil in the typically infertile Terra Preta region of Brazil – which still remains highly fertile today.

Studies done on soil treated with and without biochar show anywhere from a 10%-30% improved crop yield, and an average 22% increase in water retention. The figures vary depending on what material is used to make the biochar, the length and temperature of pyrolysis, the type of compost it was mixed with, local climate conditions, local soil conditions, and the size of the biochar particles. But there are very few studies that do not show an improvement to soil, and the soil we have in Lake and Mendocino counties takes very well to it.

“It’s basically a condominium for microorganisms,” said Chris Tebbutt, owner of Filigreen Farm in Boonville. Filigreen makes its own biochar from woody debris found on the farm’s 400 acres, and combines it with home-grown azolla-based compost to “inoculate” it with beneficial microorganisms and nutrients before it’s mixed into the soil. He says it works particularly well on his flowers, vegetables, and vineyard.

Biochar also has climate-change cred: it’s a fantastic sequesterer of carbon. Studies show that it can increase organic carbon in the soil by 44%-242%. It all comes back to the pyrolysis process, which is smokeless and traps carbon as the biochar forms. Creating biochar is actually the optimum way to dispose of woody organic matter, because the two alternatives – natural decomposition and burning – both release carbon into the air. Tebbutt feels that this is an important secondary benefit of biochar in this era of carbon-driven global warming.

“If you let a pile of wood chips decompose, the mycelium will eventually release the stored carbon back into the atmosphere. But if you take the same pile of wood and you turn it into biochar, the carbon is going to stick around in the soil for millennia,” he said. “Using biochar helps people be conscious of the dilemma we face, which is how to keep carbon in the ground, and out of the air.”

Biochar’s ability to improve water retention in soil also makes it a potential game-changer for farmers and the environment, especially considering the increasing intensity and length of drought periods in the western U.S. Although some farms such as Filigreen have their own abundant water supplies, future water scarcity is a real fear for farmers who rely on rain or underground aquifers for water.

For example, in early 2024 Barra of Mendocino decided to start making biochar to supplement the soil on one of its vineyards on the eastern hills of Ukiah. According to Martha Barra, the winery’s owner, not only is the soil on the 13-acre site less fertile than that of Barra’s Redwood Valley vineyards, but the site’s well does not provide adequate water to provide full irrigation over the long term.

So far the Barra team has made two “batches” of biochar from older, less-productive cabernet and zinfandel vines that were cleared from other parts of their property to make way for new ones. After letting the uprooted vines thoroughly dry out for several weeks, they were “baked” for several hours in a four-sided, custom-made burn container under the watchful eye of Cal Fire officials. Their plan is to mix the biochar with pomace from grapes that were crushed at the winery last fall, and apply it this coming fall after new vines are planted on the site.

To evaluate its effectiveness, Barra said they will be testing microbial activity, carbon sequestration and water holding capacity of the soil both before applying the biochar/compost mixture, and then again next year after it’s been in the ground for several months.

“We look forward to finding the correct ratio of biochar to pomace/compost to give us increased water holding capacity and enhance the microbiome,” Barra said.

While Barra, Filigreen and other farms and wineries – such as Roederer Estate in Philo, which has been making and using biochar for the last four years – produce their own black gold, not all farms have the ability or money to do so. This potentially explains why its use is not more ubiquitous locally.

Although biochar is not terribly expensive to buy, many farms and vineyards do not have room for it in their tightly-controlled budgets. The good news is that there are grants available through various federal and state entities, such as the USDA’s Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS). Local organizations like the Mendocino County Resource Conservation District (MCRCD) help connect farmers with grant funds, and with educational resources.

“We’re all about helping folks expand what they’re doing on their farms, who maybe don’t have the capital to completely support it or want to learn more about it,” said Meagan Hynes, Soil and Water Project Manager at the MCRCD. “It’s a combination of administrative help and scientific advising in terms of what may be beneficial for their farm. But a big portion of what we do is to explain the whole funding process, because a lot of the applications can be complex.”

Another obstacle to adoption of biochar is availability. Those who want to use it but can’t make their own would have to buy it from outside the area, because currently there are no local producers who sell it in bulk quantities for farmers (the only northern California merchant being Pacific Biochar in Santa Rosa). But having it trucked in from other counties or states is not necessarily economically nor ecologically sensible: aside from the obvious cost of shipping, the carbon footprint of transporting biochar via diesel- or gas-powered vehicles cancels out the carbon-sequestering benefit of creating it.

But that may change in the next couple of years as local interest in biochar grows and more entities in the region explore the feasibility of production.

For the past four years Tom Jordan, CEO of the Scotts Valley Energy Corporation (SVEC) in Lake County (chartered under the Scotts Valley Band of Pomo Indians) has been investigating economic development opportunities for the tribe. In 2021 he connected with a company based in Pittsburg, CA which has technology that generates an energy-producing material and biochar simultaneously.

In a nutshell, the company’s “pyrolysis gasification units” can heat basically any carbon-based material and break it down into two components: biochar and Syngas, the latter being primarily hydrogen, which can be burned to produce electricity. Jordan is hoping that the technology will form the basis for an energy plant that will benefit both the tribe and the environment.

“So you start with the material that comes from the soil, and you turn around and you put it back into the soil,” Jordan said. “The idea is to use forest material in Lake County as the input. We’re in the process of trying to establish a wood processing facility on a piece of property in Upper Lake that the tribe owns. We also have a power purchase agreement established with PG&E, so we would be selling the energy back to them at a wholesale rate. As for the biochar, it could be used in a number of applications. Our primary focus is energy production and the secondary focus is the biochar, but the biochar still has a big financial component to us, so we don’t ignore it or discount it as insignificant.”

“It’s basically a condominium for microorganisms.”

Chris Tebbutt, Filigreen Farm

Based on the size of the plant they plan to build, Jordan estimates that they would produce about 375 metric tons of biochar per year, which equates to more than a ton per day. He said that ideally he’d like to find a local soil or compost company who would buy it wholesale, and turn it into a “ready to spread” retail product. However, it’s still early days, and he said that selling it directly to farmers is another option, if there is enough of a market for it.

“It’d be great if I could get letters of agreement from farmers who want to take it, even if it’s just small quantities, because it could add up,” he said. “And if they were local, that would be fantastic. We’re always concerned about the carbon footprint and just how far we’d have to truck this material out. After a certain distance you haven’t made a positive impact in reducing carbon.”

Jordan said that SVEC is currently seeking funding for the project, both from traditional banks, and in the form of carbon credits. He is hoping to get the plant up and running in the next two to three years.

Perhaps even more exciting is the research being done locally at the University of California Hopland Research and Extension Center (HREC). Thanks to a Cal Fire grant to the Mendocino County Resource Conservation district, HREC Director John Bailey and his team are looking at the viability of mobile technology that would be able to make biochar at its source: local forests.

“One of the things that we have going on in our North Coast area is a lot of high fire fuel loads and excess biomass on forest lands,” Bailey said. “Right now there’s no real market for it, so government funding is the main way to pay to remove it in order to mitigate wildfire risks, and improve forest health. So potentially, biochar and related carbon sequestration credit sales could be a way to generate revenue from those fuels.”

Similar to what’s being planned at Scotts Valley Energy Corporation, the shipping container-size units that Bailey is researching would create three salable products, electricity, biochar, and carbon credits. But rather than bringing the fuel source to the machine, the machine would drive to where the fuel source already is.

“A huge cost in making biochar is transporting the biomass out of the woods, so the idea is to have these small-scale distributed units right in the forest,” Bailey explained. “You’d have a tree crew that goes out and does their work chipping wood and feeding it through, then we’d either interconnect these units to the PG&E grid and do a net metering offset or charge large-scale batteries. So you’re not transporting the biomass a long way and you’re doing more localized production.”

But Bailey acknowledges that it’s early days, and while there’s lots of promise, there are still many problems to solve. Some of the biggest are economic viability, input size, and compost timing.

“The trick is just getting the right wood chip size to produce consistent gas to run these generators,” Bailey added. “As for the biochar, we’re looking at ways to pre-treat it so that it doesn’t have the initial effect of adsorbing nutrients that are already in the soil. One of the ways that’s looking like a potential win-win is putting the biochar in a compost pile when you first make the compost, so that it absorbs excess nutrients from the compost, not the soil. This also potentially reduces the off-gassing of nitrous oxides, ammonia and other compounds from the compost pile.”

Click here to learn how to make or buy biochar for your home garden

Bailey said that his team is currently working with West Marin Compost, but he’s open to partnering with local companies such as Cold Creek Compost in Redwood Valley if and when a biochar production program becomes feasible.

As for making it all pay for itself, Bailey said that one possibility, in addition to the biochar itself and the electricity generated by the units, would be to sell carbon credits, which could prove helpful if a robust local market for biochar does not emerge.

“I think carbon sequestration credits will contribute to making distributed local biochar production more economically viable, because then you’re not limited to just selling the biochar and electricity – you can sell the credits,” Bailey added. “But that involves a very complicated process of verifying the carbon sequestration value of everything that you do, and getting layers of scientists, regulatory bodies, and market gatekeepers to sign off on it. It takes a little while, but it’s one of those behind-the-scenes things that’s necessary to make this work efficiently.”

Bailey, like Jordan, is cautiously optimistic that biochar can be locally created using this technology, but he also admits that it’s still a way off.

“It takes a little while,” Bailey said. “I’m thinking it’s probably going to be at least two to five years to get it going, and to get the market to accept it.”