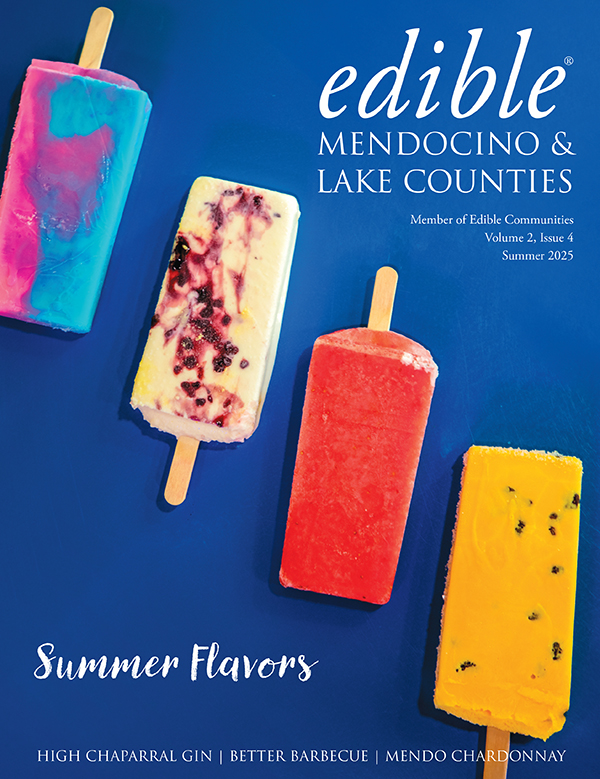

Manzanita Cooperative has ambitious plans to put native Californian foods on our tables, and transform agriculture in the process

To paraphrase an old adage: to get to know a place, you have to eat the local food.

In California, that typically means sampling farm-to-fork fare that’s grown or raised locally. This was the basis of the chef-driven “California Cuisine” movement that started in the 1980s, which capitalized on the abundance of fresh, seasonal ingredients found throughout the state.

You’d also have to try some multi-cultural fusion cuisine to truly understand California. Our melting pot state pioneered such innovative combinations as Mexican-Korean and French-Asian.

But there’s something that’s overwhelmingly overlooked in the pantheon of Californian food: native species. Which begs the question: how well can someone really know California, without ever having tasted what has naturally grown here for millennia?

With the exception of Native Americans and some dedicated home cooks, few residents or visitors to California have ever cooked or eaten anything made with ingredients derived from native flora.

But one Mendocino County-based company is well on its way to changing that. Manzanita Cooperative, an employee-owned organization, plans to bring some of California’s most plentiful native foods to a wider market. In doing so they hope to achieve two rather lofty but admirable goals: to redefine what we consider “California cuisine,” and to promote a more sustainable approach to agriculture in an era of advancing climate change.

The first products that Manzanita plans to mass produce are derived from acorns, arguably California’s most abundant— but least utilized—tree nut. Over two billion oak trees produce up to a trillion pounds of acorns per year in the state—a vast, untapped resource.

Worldwide, acorns have been a traditional food for thousands of years, across hundreds of temperate-zone cultures. The tradition remains unbroken in places like Greece, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Morocco, China, and Korea, and acorn is in fact seeing a resurgence in those countries.

In other places, such as Scotland and Ireland, the link was severed long ago. In ancient and medieval times, both the Scots and the Irish relied on acorns as a food source in times of scarcity. However, this ended by the late 18th century, after oak forests were decimated by the British Navy to source lumber for shipbuilding. This left people vulnerable to the famines that forced so many to emigrate abroad.

Acorns were also a staple of Indigenous California cuisine. Because of their ubiquity and nutritional value, acorns were used by many Native communities for daily consumption, in sacred rites and rituals, and for medicinal purposes. It is estimated that before European contact, acorn-based foods comprised 40% of the diet of local Pomo tribes in Lake and Mendocino counties. Commonly consumed foods included acorn mush, acorn soup, and acorn bread.

been a staple food in Pomo and other Native American cultures for thousands of years. (Photo by Karen Elowitt)

But beginning in the late 1700s, the culinary traditions of Native Americans were either deliberately erased or willfully ignored by European and American colonizers, who favored non-sustainable monoculture crops that were not native to the area.

“If you go back and you read accounts of the first European settlers coming here, they consistently wondered at the natural beauty of California, which they saw as a garden with no gardeners,” said Jed Wheeler, CEO and co-founder of Manzanita Cooperative. “But they failed to see that the gardeners were right in front of them! They didn’t recognize the intentionality of what Native people were doing. So they cut down the garden and killed the gardeners, and now we wonder why it’s starting to fall apart.”

“We’re trying to help bring acorn back to its rightful place in the common heritage of humanity, as a food eaten across large swaths of the world for longer than modern Homo sapiens have even existed,” Wheeler added.

Perhaps not coincidentally, Wheeler’s own family ancestry reflects this generational blind spot.

“When my great-grandfather moved to Winters, California from Glasgow, Kentucky, he chopped down an oak forest on his land and planted an almond orchard, because he knew how to farm almonds,” Wheeler said. “He didn’t know what to do with oak trees.”

It’s a pity that early settlers did not recognize the value of acorns, because in addition to their ubiquity, they are a nutritional superfood. Nutrient-dense and calorie-rich, acorns contain substantial amounts of protein, potassium, calcium, iron, magnesium, phosphorus, vitamins A, E, C and B6, and antioxidants.

“Acorn flour and acorn starch are versatile, gluten-free, low-glycemic, and very, very nutritious,” Wheeler explained. “Their high protein content is particularly helpful for vegetarians, who sometimes struggle to get the protein that they need. Acorn is a complete protein.”

The potential market for acorn flour and acorn starch is huge, as they can be used in the same recipes—and in the same ratios— as pantry staples such as wheat flour and corn starch.

“Acorn starch is a thickener, and it can be used as a replacement for corn starch,” Wheeler explained. “It’s got such a wonderful subtle nutty flavor. It also makes the best breading for fried chicken that you’ve ever had, and I really, really like it for desserts. And acorn flour is an excellent substitute for traditional flour in recipes for pasta, breads, cakes, cookies, and stews.”

But acorn products haven’t been more widely adopted because, to put it simply, the production process is extremely labor-intensive. All of the acorn flour currently produced in California is ground by hand or with small-scale equipment. It is tedious and time consuming to make at home, and it translates to very steep prices for the retail buyer.

“It takes an hour of work to produce a pound of acorn flour by hand,” Wheeler noted. “A lot of people try it out, think it’s cool, and say, ‘okay, that was delicious, but way too much work.’”

Acorn flour that’s available for retail sale costs around $50 per pound and is typically only available online. Acorn starch can be found more easily and at a much cheaper price, but it’s sourced almost entirely from the thriving Korean and Chinese acorn industries, not from native Californian trees.

Manzanita plans to produce native acorn products cheaply, quickly and efficiently by leveraging existing processing machinery. “If you really want to change the way that we eat and the types of flours we consume, it has to be mass produced,” Wheeler explained. “We are testing machinery that was created for California’s $8 billion tree nut industry, which we are adjusting for acorns.”

The acorns will be processed into whole leached acorns, acorn flour, and acorn starch in a facility that Manzanita is hoping to locate somewhere in Mendocino County, and have operational by September 2025. The machinery is currently being tested and fine-tuned with a “beta” crop of 500 pounds of acorns.

“We’re currently comparing the impacts of different processing techniques,” Wheeler said. “Once we know what works best, then we’ll have a lot more information to go to market. We’re also testing some really interesting proprietary technology that we’ve developed specifically around the leaching process.”

Leaching, an essential step in acorn processing, involves using water to remove the tannins from the nuts—a substance that would otherwise make acorns toxic, and too bitter to eat. Manzanita has plans to re-purpose the tannins and other byproducts, with the goal of having a zero-waste production stream.

“We’re trying to make sure that we use every part of the nut,” Wheeler explained. “Tannins are a two-and-a-half-billion-dollar industry in the U.S., and they’re used in everything from pizza boxes to pressure-treated lumber to cancer medicine. So we can sell our main waste product as a valuable product in its own right. There are also some potential uses for the leftover acorn shell material, which can be turned into packaging material, or even biochar.”

Employing local Indigenous people at the processing facility is another priority for Manzanita. The company plans to start with 15 employees, and grow to 85 by 2030.

“I’m hoping to recruit as many people as possible from our local Indigenous communities,” Wheeler said. “I think it’s really important, given the historical linkage between acorns and Native Californians, to offer those jobs to our Indigenous neighbors, especially since so many of the reservations have such unacceptably high unemployment and so few opportunities.”

Various species are being considered, including tanoak, valley oak, blue oak, and black oak. UC Davis is funding a study to analyze the nutritional values of the different types, and the processing equipment is being tested with different varieties. The intent, however, is not to choose one species, but to process multiple species. Each has different characteristics, a different harvesting “window,” and a different flavor profile, like grapes.

As far as harvesting, the acorns will be sourced from existing trees in Mendocino, Lake and Humboldt counties, on land that is contracted from private landowners. The company currently has 2500 acres with five landowners under contract, with plans to add 10 times that many in the next few years.

Harvesting acorns from existing trees is part of Manzanita’s two-pronged effort to help landowners while protecting oak trees, which are under threat throughout the state.

“Much of California’s native oak forest is on privately held lands,” Wheeler said. “And it’s shrinking because there’s this economic pressure to cut and clear it for logging revenue, farming, housing, and so on. We are helping landowners to monetize their intact old-growth oak forest and remove that pressure to cut the trees down.”

“Oak forests are incredibly important to our ecosystem,” Wheeler added. “They’ve got more biodiversity than any other biome in California, with over 6000 species.”

Manzanita is careful to harvest not only sustainably, but with sensitivity toward Indigenous communities.

“We take 25% or fewer of the nuts from any given site, to ensure that there are enough left behind for replanting, and for the animals that rely on them,” Wheeler said. “We are also harvesting only on privately owned lands where Native harvesting has not been historically permitted—not on public or tribal lands. We’re working really hard to make sure we’re good neighbors.”

Although wild harvesting is Manzanita’s current method of obtaining acorns, the company is also planning to sustainably farm oak trees. In fact, their vision is to one day replace most orchards in the state that grow non-native tree nuts (such as almonds and pecans) with oak orchards.

“We will be planting oak trees eventually, but we’re not going to try to recreate a monoculture system with a different tree,” Wheeler said. “It will be done using a polyculture agroforestry approach with multiple crops growing together. Most almond orchards are actually sitting on former oak forests, so it would be a form of habitat restoration.”

One of Wheeler’s personal goals is to buy his great-grandfather’s almond orchard in Winters and replant the oak forest that used to be on the land.

If Manzanita successfully scales up according to its business plan, it could save California over eight trillion gallons of water per year.

“Almond orchards use 17% of California’s water,” Wheeler noted. “You save 400 gallons of water for every pound of acorn flour produced in lieu of almond flour. Replacing almonds with acorns would be transformative for California’s water supply and do so much to support river restoration efforts and climate adaptation.”

Manzanita’s first-year goal is to harvest 96 tons of acorns, which will be processed into about 33 tons of food. In each successive year they plan to produce five times the amount of the previous year.

Wheeler acknowledges that achieving substantial sales volume hinges primarily on availability, because he feels that the demand is already there.

“There’s actually a lot of interest in acorn flour from consumers in California,” Wheeler said. “A lot of people would like to try it, and others have tried it somewhere and then couldn’t get it again. But if you really want sustainable foods to be widely adopted, you have to make it easy for people to buy them.”

Manzanita intends to make its products not only affordable, but available directly to consumers through Amazon.com, through the Manzanita Cooperative website, and potentially through local grocery stores.

“We’re hoping to launch with a price pegged either even with—or slightly above—the price of almond flour, and bring it directly to consumers,” Wheeler explained. “The plan is very much to bring acorn flour to the masses through those different channels.”

The company also plans to make acorn products available at below-market rates to local Indigenous communities. “Right now we’re working with a couple of different Indigenous-led organizations—including the California Indian Museum and Cultural Center (CIMCC) to help source acorn products for their food programs,” Wheeler said. “We’re going to offer these products to local tribal groups at pretty steeply discounted wholesale prices. And I’m hoping that we’re able to do that at a relatively large scale relatively quickly, because being cut off from their land and the loss of access to traditional foods has had terrible health consequences for Indigenous people. I can’t make a land-back program happen, but I can help put food in the hands of people who want to eat it.”

The CIMCC, which is based in Santa Rosa, plans to buy acorn flour for its Acorn Bites program. This microenterprise makes and sells small acorn-based snacks, and the proceeds benefit educational and cultural advancement of Indigenous youth in Sonoma and Lake counties. The program has experienced supply chain issues in recent years as some of its main acorn flour vendors retired.

“The thing that needs to happen for us to try to create more acorn bites, to scale up our business and make it more accessible, is we need more acorn flour,” said Nicole Myers- Lim, Executive Director of the CIMCC. “Our partnership with Manzanita was very natural because we were looking to increase that flour supply, and Manzanita was seeking to provide it.”

Lim also sees acorn flour fitting in at the traditional food incubator that the CIMCC is creating. It will function as a teaching kitchen, a place to process and store traditional foods, and a place where native food vendors can grow their businesses.

“I think partnerships like ours demonstrate the opportunity for Native and non-Native organizations to work together in a collective effort that benefits our tribal community by improving cultural resources and nutrition,” Lim added. “What Manzanita is doing is going to create stability that’s really going to grow more Native food centers and that’s going to benefit all of our community.”

While the CIMCC has no specific preference for which oak trees its acorn flour supply comes from, Manzanita plans to cater to organizations that do have a preference by making products from different species.

“You talk to people in some [Indigenous] communities and they’re like, ‘yes, this is our acorn,’” Wheeler said. “Then you talk to people in other communities, and they say ‘oh, those are garbage acorns.’ People have very strong feelings about which acorns they want to eat.”

A little further into the future, the company plans to expand into wholesale opportunities in different industries.

“I’m having discussions with a company right now that wants to do a beverage derived from acorn,” Wheeler said excitedly. “There are also some really fantastic opportunities in commercial baking in particular, because the moisture that acorn flour retains keeps baked goods moist longer so that they don’t go stale as quickly.”

To help raise the acorn’s public profile, Manzanita plans to launch an educational website, EatAcorn.com, which will go live in January 2025.

Created in collaboration with the CIMCC and several other organizations, the site will showcase Indigenous cuisines from around the world that use acorns, with an emphasis on acorn recipes from California. It is being edited by Sara Calvosa-Olson, an award-winning Native American chef and cookbook author.

“One of the things we want to do with EatAcorn. com is teach people how to prepare foods themselves,” Wheeler said. “I think that’s actually really important because we live in a world of increasing food insecurity, so teaching people how to use and process and eat this abundant food is an important skill for people to have.”

Manzanita does not intend to stop at acorns. In fact, acorns are just the first step in its ambitious plan to widen the adoption of native species and revolutionize how agriculture is done in the state. The company’s next project is gene-informed rapid breeding.

In a nutshell, gene-informed rapid breeding is a technology that uses genetics to quickly improve crops for use in agriculture. By doing sophisticated and detailed genetic testing on every generation of a crop, then leveraging the results to pinpoint the best plant varieties to cross-breed with to get the desired result, gene-informed rapid breeding allows scientists to create hybrid species in a fraction of the time that traditional breeding takes. It does not involve modifying or changing the genes themselves.

It has been used for years to create new domestic crops from existing ones. But Manzanita plans to use it in a different way: to create new domesticated crops from wild species, hopefully in the next couple of years. While domestication of wild species for use in farming is not a new concept, it previously took decades to accomplish.

“A century ago, when Elizabeth White domesticated the blueberry on the East Coast, it took her 30 years to do it,” Wheeler said. “And more recently, the folks who developed Kernza at The Land Institute in Kansas spent about 20 years breeding for that project.”

“As far as I’m aware, we are the only company in the world attempting to commercialize domestication and diversify crops by rapidly domesticating new species,” Wheeler added.

Having a diversity of crops available for cultivation is the ultimate hedge against climate change, according to Wheeler. With crop failures happening around the world due to extreme heat, water shortages, and increasingly unpredictable weather patterns, being able to turn to a different crop when conditions are no longer ideal for the existing one is a wise strategy.

“There are 30,000 species in this world that can provide food for humans, but only 174 of them are grown commercially,” Wheeler explained. “That genetic bottleneck creates real risk in a changing climate, because all of those 174 are adapted for the climate as it was, and to some degree as it is now. But they’re not adapted for the climate as it will be. And we’re seeing more and more frequent disruptions. One of the most powerful things that we can do is adopt the same strategy that an investor would use—diversification. If you’ve got a bunch of assets, some of them may go belly up. But if you’ve diversified, you won’t lose everything.”

With a grant from the National Science Foundation, Manzanita is currently working on domesticating lupine (also known as lupin), a flagship native California plant species. You’ve probably been seeing the purple flower-adorned bushes for years, without realizing it was lupine.

Lupine produces high-protein, high-nutrient lupini beans, which are similar to soybeans. Like acorns, lupini beans have been consumed by various cultures around the world for millennia, including some Native American communities. It is a staple food in places like Italy, Brazil, Portugal and Egypt, where it is currently domesticated and cultivated. But not in California.

Manzanita is developing a new native-derived, low-alkaloid lupini bean with the superior drought adaptation characteristics inherent to California’s lupine species. Research on five different species is currently taking place, primarily at a company lab in Utah.

“California has 120 species of lupine, out of the 220 in the world, but none of them has ever been domesticated,” Wheeler said. “And none of the other lupines in the world have the California lupine’s drought adaptations.”

The idea is for lupini beans to become an alternative to soybeans, which today constitute 75% of the global plant-based market. In addition to being very thirsty, soybeans are problematic in other ways: the vast majority grown in the U.S. are genetically modified, and many imported beans are grown via slash-and-burn agriculture.

Manzanita’s initial research has shown that lupini could outperform soy as a food source for both humans and livestock, without the environmental consequences of soybeans.

The company’s bio-native version would first be planted as a winter crop for rotation in existing fields. As a nitrogen fixer, it would improve soil quality. Five or 10 years down the line the plan is to plant it as a ground cover on farmland that was previously oak savanna. To preserve local genetics it would ideally be planted between oak trees sourced from nearby wild populations, as well as bay laurels, and newly domesticated crops including native-derived grains, currants, hazelnuts. This would help reestablish biodiversity, rebuild native habitat, reduce water consumption, and crucially, act as a habitat for pollinator species.

“Lupine, which grows naturally amongst oak grasslands, is a keystone species for native pollinators,” Wheeler said. “In fact, one of the key elements of our breeding program is to ensure that the domesticated version we produce does not have a radically different flower morphology from the wild version, because we want to ensure that the plant retains its habitat value for pollinator species.”

Field trials will begin in 2026, primarily in Mendocino County, but the company will also contract with growers in other parts of California to test the plant’s viability in a variety of climates. When commercial production is ready to start, Manzanita plans to launch a grower’s cooperative (also based in Mendocino County) to grow and harvest the crop. Manzanita is not able to share too many other details—particularly of the R&D, since it is proprietary—but the company is certain that it is on the right track toward building a more sustainable way of doing agriculture in California, and has big plans to expand its remit.

“We’ve got a spreadsheet with 200 more species that have a lot of agricultural potential, and can be bred to produce food at the commercial scale,” Wheeler said.

If it all sounds quite ambitious, that is exactly the point: big problems need big solutions.

Wheeler had long been concerned about climate-driven food insecurity, the loss of biodiversity caused by over 200+ years of bad land management, and non-native monoculture. He knew something needed to be done to combat it, and soon.

“The deliberate destruction of indigenous land management practices because of racism and colonization are at the root of a lot of the challenges that we face as a state now,” he noted. “For example, why do we have wildfires? Invasive non-native species are actually one of the biggest drivers of that. The forests haven’t had regular controlled burn cycles for generations. And why do we have so many water shortages? Because rivers and aquifers are depleted by water-intensive crops such as almonds and alfalfa.”

He deduced that one way to tackle these issues was to make agriculture better through native species. Since he didn’t see anyone else doing it, he decided to start Manzanita.

“We did not choose a small problem to try to solve,” Wheeler admits. “None of our native crops are grown commercially, so we started the company to show that there’s important, valuable, climate-adapted food here that’s super nutritious. And starting with those two species [oak and lupine], we want to also create the beginning of a polyculture system.”

Of course, Manzanita Cooperative does not run solely on one man’s enthusiasm and experience. In addition to Wheeler, who has a background in technology, product development, gardening, and native habitat restoration, Manzanita’s six other team members bring over 130 years of collective experience in sustainability, conservation, horticulture science, marketing, manufacturing, operations, bioinformatics, and education.

The company is currently funded through a combination of private investors and public grants. As with the great majority of startups, finding funds can be a tough slog. Wheeler spends a lot of his time writing grant applications, courting investors, and sometimes facing disappointment when dollars are denied.

“The biggest barrier for us in funding is that nobody’s done this type of work before in California,” Wheeler lamented. “Once we’ve done it, we’ll have proven it’s possible. But getting there is the hard part.”

But unlike most other founders of scrappy startups, Wheeler is not trying to get rich doing what he does with Manzanita. As a worker-owned cooperative, he and the rest of the team are motivated not by profit, but by a love for native species and a desire to improve the environment by changing how we grow food.

“Our culture has unknowingly terraformed California with a non-native biology that is not adapted to our unique climate,” Wheeler said. “So if we can do the opposite, and instead of trying to adapt the environment to agriculture, adapt agriculture to the environment, we can create a fundamentally more resilient way of producing.”

“We just want to make the world better,” Wheeler added. “It would be a really, really big win for Manzanita to be the catalyst that pushes California —and the world, longer term—towards more sustainable, climate-adapted native crops. I think that the North Coast can become the capital of an industry built around native tree nuts and other species.”

Manzanita Cooperative is currently seeking additional backers to help support and expand its work. If you are interested in becoming an investor, please reach out using the contact form at manzanitacooperative.com.