Hopland’s Terra Sávia is the first facility in the country to pilot vermifiltration of olive oil mill wastewater

Visitors to Terra Sávia, the winery and olive oil maker in Hopland, can find an array of animals on the property: in addition to the donkeys, horses, goats, birds, sheep and bull in the animal sanctuary, there are also resident dogs and cats.

Then there are the worms. While not as cute and cuddly as the other creatures on the farm – who spend their days at leisure – the worms do a very important job: they filter and clean the wastewater from the winemaking process.

The worm population recently doubled, thanks to a new batch that was brought in to do yet another job: filter the wastewater from Terra Sávia’s olive oil milling operation.

While vermifiltration of wastewater derived from winemaking is fairly common at sustainability-minded farms around the country and locally, Terra Sávia is the first in the U.S. to try it on olive mill wastewater (OMW).

The company is doing so in partnership with BioFiltro, the same firm that provided the vermifiltration system for its winery. Terra Sávia approached BioFiltro earlier this year about doing vermifiltration on the 500,000 gallons of OMW the olive mill produces every year, but had no way to sustainably process.

“We’d been using it for dust control on our dirt roads in the summer, but there wasn’t really much else we could do with it,” said Carlos Suarez, Director of Operations at Terra Sávia.

BioFiltro enthusiastically agreed to a three-month pilot, knowing that several studies had shown that vermifiltration could be successfully achieved with OMW.

“There was literature on using vermifiltration for olive mill wastewater that looked promising,” said Sarah Haupt, a sales engineer at BioFiltro. “So that was enough for us.”

BioFiltro, which was founded in Chile in 1990 and is now headquartered in Davis, CA, is a wastewater treatment provider that developed a patented Biodynamic Aerobic (BIDA®)vermifiltration system. They have worked on over 200 projects across nine counties, including 25 operational plants in California, Oregon, Washington and Texas that process wastewater from rural sanitation facilities, wineries, the food industry, dairy farms–and now, olive oil mills.

Handling of OMW is an ongoing concern for olive mills. Unless it is treated, it can’t be used on crops, soil, or for animals because it contains high quantities of fat, grease, phenolic compounds, and other suspended solids that can be toxic to plants, pollute aquifers, and degrade the quality of soil.

“If [OMW] gets discharged to a river or surface soil, it’s going to take so much oxygen out of that soil or water that it’s going to be detrimental to the environment,” Haupt explained. “The solids can cause sealing on the soil, which creates odor problems. It also tends to be high in total nitrogen, which is especially a problem here in California. We already have a lot of nitrates in our groundwater, which isn’t great as far as water quality is concerned.”

Some olive mills find ways to safely use OMW on non-agricultural land, as Terra Sávia previously did. Others store it in evaporation ponds, then haul the sludge that is left behind to a landfill. Still others recycle it for agricultural use.

Besides vermifiltration, there are several ways to make OMW safe for use on farms. Chemical treatment and membrane filtration are the two most common. However, neither of these methods are fully environmentally sustainable. BioFiltro was keen to test vermifiltration at Terra Sávia, as both companies are firmly committed to sustainability.

“Vermifiltration is actually the most natural way to treat olive mill wastewater,” Haupt said. “It regenerates water, reduces greenhouse gas emissions, and revives soil.”

Although the composition of OMW is somewhat different from that of winery wastewater, the vermifiltration process is nearly identical. The only real differences are in the type of material used to build the filtration units and their size, which can vary widely depending on the amount of wastewater being filtered.

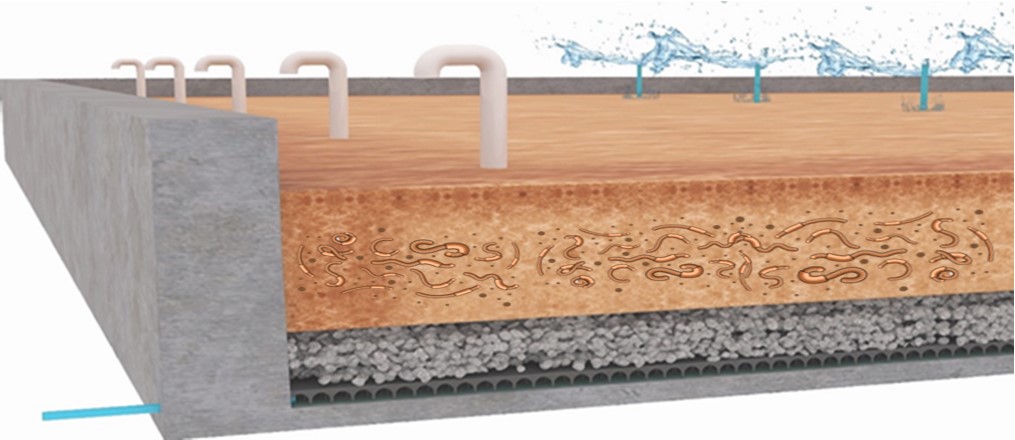

The system that BioFiltro installed at Terra Sávia is about 12 cubic yards and can process about 20 gallons of OMW in four hours. It actually has two parts: a control unit, which aerates the water, filters out larger solids, and adjusts the pH to a level that is amenable to the worms; and another larger unit where the worms work their magic.

The second unit, which looks a bit like a double-decker cargo shipping container, has two identical stacked tiers. Each has a bottom drainage layer, a middle layer with soil, microbes and earthworms, and a top layer of wood chips (see inset diagram). The wastewater is pumped in from the control unit and sprinkled evenly across the surface of the wood chips via a built-in irrigation system. It then percolates through the wood chips into the middle soil layer, where the worms–specifically Eisenia andrei, also known as the “red wiggler worm”–consume the solids and other substances in it. The resulting “cleansed” water then drips onto the sloped bottom, and drains out through exit pipes.

In addition to the detoxified water, the system also produces worm poop, otherwise known as vermicompost. Vermicompost is a great soil amendment for crops, as it’s rich in microbes and improves nutrient cycling, water retention, and soil health. It also reduces greenhouse gas emissions.

“There’s no sludge in our systems,” Haupt said. “The biofilm that dies and would otherwise become sludge in a pond or a membrane bioreactor system turns into vermicompost in a vermifiltration system. So you still have a solid to deal with, but it’s a much more stable, valuable, nutrient-rich natural fertilizer rather than having this stinky sludge that you’re hauling to a landfill.”

Vermifiltration is also more energy efficient than other methods of OMW treatment, because no machinery is required to maintain it – the worms do all the work.

“The worms create drainage channels for the water to percolate through,” Haupt said. “They’re passively aerating the system for us. It’s much more energy-efficient than some of the other technologies for this type of treatment, which rely on mechanical aeration to move the sludge around and keep it aerobic.”

After the three-month trial is complete, BioFiltro will test and evaluate the wastewater, then make any adjustments necessary to the system before Terra Sávia purchases and implements it on a permanent basis. The goal is to use the filtered water to irrigate the 25-acre vineyard, the gardens, and the fields where alfalfa is grown for the animals.

This latest sustainability measure adds to a long list at Terra Sávia. The property is 100% off-grid, relying on water from freshwater springs, and power from solar and wind energy. The vineyards and orchards are certified organic and fish-friendly, and are cultivated to make as little impact as possible to the environment.

In every way, vermifiltration is a perfect model of sustainability: it safely returns water to the very ground that it originally sprang forth from, after being cleaned by thousands of Earth’s own creatures. Very fitting indeed for a company whose own name intentionally suggests reverence toward nature, and translates to “wise earth.”

Terra Sávia is located at 14200 Mountain House Road in Hopland. It is open for tastings and tours seven days a week. For more information about Terra Sávia (and its associated brands Olivino and Ettore), visit terrasavia.com.