A decade ago the Shannon family learned that the 19th-century roots of Lake County’s wine industry were, quite literally, lurking in their property, connecting them to a winemaking legacy that they chose to honor in a most delicious way

Lake County has been home to winemakers since the first non-Indigenous settlers arrived, not long after the Gold Rush.

The industry began to emerge back in the 1860s, spearheaded by European immigrants who were attracted by the region’s warm, dry climate, and who often brought vines with them from their homelands. The most famous early winemaker was Lillie Langtry, the British actress and socialite who established Langtry Farms in 1888 in the hills above Middletown.

As of 2024 Lake County has become one of the most exciting and fast-growing wine regions in the country, with eight AVAs, over 30 wineries, and over 150 years of almost-continuous production—

minus 13 dry years during Prohibition.

Shannon Ridge, established in 1996, is one of the wineries that helped put Lake County on the map. Located on 2000 acres of rolling hills above Clearlake Oaks, it is a decidedly 21st century operation that uses regenerative organic farming principles and progressive labor practices to protect both the planet and employees, while coaxing the best flavors from the grapes.

But despite its future-facing ethos, about a decade ago the Shannon family learned that the 19th-century roots of Lake County’s wine industry were, quite literally, lurking in their property, connecting them to a winemaking legacy that they chose to honor in a most delicious way.

The story starts in the early 1870s, when Martin Ogulin and his family emigrated from the Austro-Hungarian Empire (specifically the area that is now Croatia) to Lake County via Ellis Island. These early pioneers set up a homestead in the High Valley hills that came to be known as Circle O Ranch (or the Ogulin Estate) and gradually grew to include a small house, a horse barn, a winemaking facility, and a hand-dug well. According to family oral history, the family raised livestock, grew walnuts and hay, and made wine from Zinfandel and Muscat grapevines they had brought with them from Croatia.

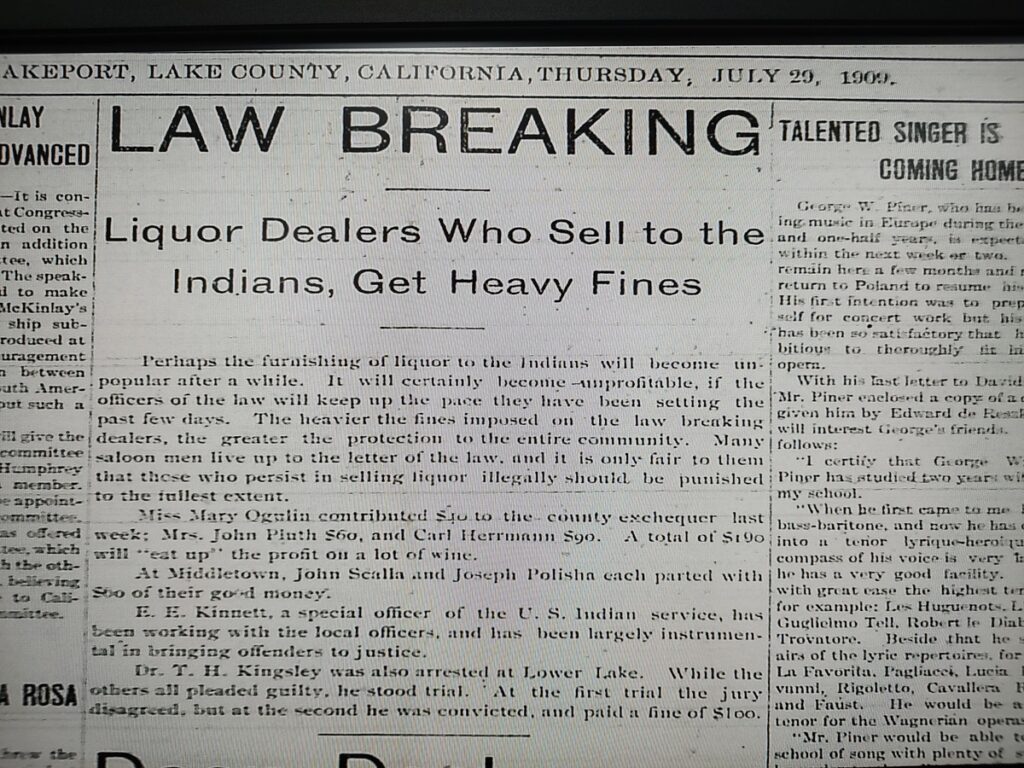

The historical record is a little spotty regarding how many acres of grapes they cultivated, and whether they sold or bartered the wine they made. The name “Ogulin” does not turn up in official records of early winemakers in the county, but a tantalizing clue does appear in a 1909 article in the Lake County Bee, which reported that several “dealers” had pleaded guilty to illegally selling liquor to Indians. One of the offenders, Miss Mary Ogulin, was fined the hefty sum of $40, which, according to the article, would surely “eat up the profit on a lot of wine.” So, even though the evidence is scant, it is probably safe to say that Circle O Ranch can be counted among Lake County’s earliest wineries—in a manner of speaking.

Fast forward to 2013, when Clay and Angie Shannon acquired 100 acres of the Circle O Ranch from Grace and Harold Ogulin, a third-generation descendant of Martin Ogulin. The property, which was adjacent to the Shannons’ existing land, offered the couple the opportunity to expand their vineyards and grow their business. In fact, they already leased 18 acres from the Ogulins and grew Cabernet Sauvignon grapes on it, so they were well aware of the high quality of the volcanic soil.

They were also aware of the trees, vines, streams and long-abandoned buildings that existed on the site, and even the handful of old Zinfandel vines that had presumably been planted by previous generations of Ogulins. What they were not aware of was the hidden treasure that lay concealed among a centuries-old tangle of weeds, dirt, and wire.

In 2014, while clearing up a messy, scrubby section of the site to make way for new vineyards, one of the Shannon crew hit a metal bedpost that was half-buried amongst some bushes. Thinking it was odd, he jumped off his tractor to investigate.

What he found when he pushed the bushes aside surprised everyone: a thick, gnarled, elbow-shaped length of grapevine. It was almost unrecognizable because not only was it hidden amid a bunch of

barbed wire and other debris, but it had almost no leaves on it. Furthermore, it was not growing in the typical grapevine shape. Most of it was crawling horizontally across the ground, and parts of

it were even buried under the soil.

Upon taking a closer look, Clay Shannon recognized that it was not a native Vitis riparia vine, but rather a Vitis vinifera variety, which is common in central Europe, the Middle East and North Africa.

It was a lightbulb moment for him. He deduced that maybe this was one of the vines that the Ogulins had brought with them from their central European homeland and planted back in the 1870s. So he set out to test his theory.

After nursing the vine back to health a bit by watering and protecting it from the elements, eventually the Shannon crew was able to grow enough leaf and tissue matter to send for testing and analysis at UC Davis. When the results finally came back weeks later, it was revealed to be a cinsault (also spelled

“cinsaut”) vine, a rosé variety that is indeed commonly found in Central Europe. Testing also confirmed that it dated back to roughly the 1870s, just as Shannon had guessed.

Shannon, along with Joy Merrilees, Vice President of Production at Shannon Ridge, realized that cinsault would actually be a perfect grape to cultivate at the vineyard. Because of its drought tolerance, it’s been a popular grape in North Africa, the Middle East, the south of France and other hot, dry regions for hundreds, if not thousands of years.

Clearly it was hardy enough to withstand Lake County’s drought-prone climate—for 150 years, no less.

“When we realized it was cinsault, we were like, oh, my gosh, this is perfect!” Merrilees explained. “And it was already here! This is exactly what we’re trying to do at Shannon Ridge.”

However, since cinsault vines are susceptible to disease, Shannon and Merrilees spent another two years waiting for the vine to grow enough tissue to send for virus testing. Miraculously, the results were negative.

“It’s amazing that the vine had no viruses, because it had been living in the ground since the 1870s with no water, no protection, nothing,” Merrilees marveled.

In 2017 they started the long, complex process of cultivation, with the help of Guillaume Grapevine Nursery in Knights Landing. Nodes were cut from the vine, grafted onto rootstock, propagated, then planted. Starting with about 10 buds and expanding exponentially each year, by 2023 they finally

had a full acre of mature vines. The first harvest (approximately 1,000 vines) took place in August 2023.

After harvesting, the saigneé method was used to gently bleed the juice off the crushed grape must. This method reduces skin contact time, gives flavor and texture to the fruit, and enhances the natural acidity of the grape. It was then blended with 62% grenache, a percentage that Merrilees says will drop in successive years as more cinsault becomes available. A second acre, which was planted last fall, will definitely help in that regard.

The wine was aged for five months in the bottle, then in May 2024, after nine years in the making—or 150 years, depending on how you look at it—700 cases of 2023 Mother Vine Rosé hit the market.

It’s fresh and delicate, with a floral component and notes of rhubarb, tart raspberry, cherry, strawberry, and Meyer lemon. The exquisite artwork on the bottle, created by Angie Shannon herself, is similarly delicate and floral.

The original vine, the “mother” of all the new vines, now flourishes in its original spot, overlooking its spawn. Fully rehabilitated and gloriously leafy, it’s about six feet wide and four feet high, and

produces copious amounts of fruit that is incorporated into the wine. It’s protected by a circular two-foot high rock wall barrier which doubles as a seat, and is a great place to enjoy a glass.

If you look north from the vineyard you can still see the Ogulin family’s original one-bedroom wooden house, horse stable, and wine cellar. All the structures have managed to withstand the centuries, just like the vine.

It’s fun to imagine that Martin Ogulin—who no doubt toiled for weeks, if not months, to carry his family and his vines across two continents and an ocean—would have been tickled rosé pink to know that his vine had proved to be just as much a survivor as him. And to know that his family’s winemaking legacy was being so lovingly and symbolically carried on by the latest generation of Lake County winemakers.

Learn more about the Shannon Family of Wines, including how to buy the 2023 Mother Vine Rosé, at shannonfamilyofwines.com.